The house on Grettisgata Street, in Reykjavik, is a century old, small and white, situated just a few streets from the North Atlantic. The shifting northerly winds can suddenly bring ice and snow to the city, even in springtime, and when they do a certain kind of silence sets in. This was the case on the morning of March 30th, when a tall Australian man named Julian Paul Assange, with gray eyes and a mop of silver-white hair, arrived to rent the place. Assange was dressed in a gray full-body snowsuit, and he had with him a small entourage. “We are journalists,” he told the owner of the house. Eyjafjallajökull had recently begun erupting, and he said, “We’re here to write about the volcano.” After the owner left, Assange quickly closed the drapes, and he made sure that they stayed closed, day and night. The house, as far as he was concerned, would now serve as a war room; people called it the Bunker. Half a dozen computers were set up in a starkly decorated, white-walled living space. Icelandic activists arrived, and they began to work, more or less at Assange’s direction, around the clock. Their focus was Project B—Assange’s code name for a thirty-eight-minute video taken from the cockpit of an Apache military helicopter in Iraq in 2007. The video depicted American soldiers killing at least eighteen people, including two Reuters journalists; it later became the subject of widespread controversy, but at this early stage it was still a closely guarded military secret.

Assange is an international trafficker, of sorts. He and his colleagues collect documents and imagery that governments and other institutions regard as confidential and publish them on a Web site called WikiLeaks.org. Since it went online, three and a half years ago, the site has published an extensive catalogue of secret material, ranging from the Standard Operating Procedures at Camp Delta, in Guantánamo Bay, and the “Climategate” e-mails from the University of East Anglia, in England, to the contents of Sarah Palin’s private Yahoo account. The catalogue is especially remarkable because WikiLeaks is not quite an organization; it is better described as a media insurgency. It has no paid staff, no copiers, no desks, no office. Assange does not even have a home. He travels from country to country, staying with supporters, or friends of friends—as he once put it to me, “I’m living in airports these days.” He is the operation’s prime mover, and it is fair to say that WikiLeaks exists wherever he does. At the same time, hundreds of volunteers from around the world help maintain the Web site’s complicated infrastructure; many participate in small ways, and between three and five people dedicate themselves to it full time. Key members are known only by initials—M, for instance—even deep within WikiLeaks, where communications are conducted by encrypted online chat services. The secretiveness stems from the belief that a populist intelligence operation with virtually no resources, designed to publicize information that powerful institutions do not want public, will have serious adversaries.

Iceland was a natural place to develop Project B. In the past year, Assange has collaborated with politicians and activists there to draft a free-speech law of unprecedented strength, and a number of these same people had agreed to help him work on the video in total secrecy. The video was a striking artifact—an unmediated representation of the ambiguities and cruelties of modern warfare—and he hoped that its release would touch off a worldwide debate about the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. He was planning to unveil the footage before a group of reporters at the National Press Club, in Washington, on April 5th, the morning after Easter, presumably a slow news day. To accomplish this, he and the other members of the WikiLeaks community would have to analyze the raw video and edit it into a short film, build a stand-alone Web site to display it, launch a media campaign, and prepare documentation for the footage—all in less than a week’s time.

Assange also wanted to insure that, once the video was posted online, it would be impossible to remove. He told me that WikiLeaks maintains its content on more than twenty servers around the world and on hundreds of domain names. (Expenses are paid by donations, and a few independent well-wishers also run “mirror sites” in support.) Assange calls the site “an uncensorable system for untraceable mass document leaking and public analysis,” and a government or company that wanted to remove content from WikiLeaks would have to practically dismantle the Internet itself. So far, even though the site has received more than a hundred legal threats, almost no one has filed suit. Lawyers working for the British bank Northern Rock threatened court action after the site published an embarrassing memo, but they were practically reduced to begging. A Kenyan politician also vowed to sue after Assange published a confidential report alleging that President Daniel arap Moi and his allies had siphoned billions of dollars out of the country. The site’s work in Kenya earned it an award from Amnesty International.

Assange typically tells would-be litigants to go to hell. In 2008, WikiLeaks posted secret Scientology manuals, and lawyers representing the church demanded that they be removed. Assange’s response was to publish more of the Scientologists’ internal material, and to announce, “WikiLeaks will not comply with legally abusive requests from Scientology any more than WikiLeaks has complied with similar demands from Swiss banks, Russian offshore stem-cell centers, former African kleptocrats, or the Pentagon.”

In his writing online, especially on Twitter, Assange is quick to lash out at perceived enemies. By contrast, on television, where he has been appearing more frequently, he acts with uncanny sang-froid. Under the studio lights, he can seem—with his spectral white hair, pallid skin, cool eyes, and expansive forehead—like a rail-thin being who has rocketed to Earth to deliver humanity some hidden truth. This impression is magnified by his rigid demeanor and his baritone voice, which he deploys slowly, at low volume.

In private, however, Assange is often bemused and energetic. He can concentrate intensely, in binges, but he is also the kind of person who will forget to reserve a plane ticket, or reserve a plane ticket and forget to pay for it, or pay for the ticket and forget to go to the airport. People around him seem to want to care for him; they make sure that he is where he needs to be, and that he has not left all his clothes in the dryer before moving on. At such times, he can seem innocent of the considerable influence that he has acquired.

Sitting at a small wooden table in the Bunker, Assange looked exhausted. His lanky frame was arched over two computers—one of them online, and the other disconnected from the Internet, because it was full of classified military documents. (In the tradecraft of espionage, this is known as maintaining an “air gap.”) He has a cyber-security analyst’s concern about computer vulnerability, and habitually takes precautions to frustrate eavesdroppers. A low-grade fever of paranoia runs through the WikiLeaks community. Assange says that he has chased away strangers who have tried to take his picture for surveillance purposes. In March, he published a classified military report, created by the Army Counterintelligence Center in 2008, that argued that the site was a potential threat to the Army and briefly speculated on ways to deter government employees from leaking documents to it. Assange regarded the report as a declaration of war, and posted it with the title “U.S. Intelligence Planned to Destroy WikiLeaks.” During a trip to a conference before he came to the Bunker, he thought he was being followed, and his fear began to infect others. “I went to Sweden and stayed with a girl who is a foreign editor of a newspaper there, and she became so paranoid that the C.I.A. was trying to get me she left the house and abandoned me,” he said.

Assange was sitting opposite Rop Gonggrijp, a Dutch activist, hacker, and businessman. Gonggrijp—thin and balding, with a soft voice—has known Assange well for several years. He had noticed Assange’s panicky communiqués about being watched and decided that his help was needed. “Julian can deal with incredibly little sleep, and a hell of a lot of chaos, but even he has his limits, and I could see that he was stretching himself,” Gonggrijp told me. “I decided to come out and make things sane again.” Gonggrijp became the unofficial manager and treasurer of Project B, advancing about ten thousand euros to WikiLeaks to finance it. He kept everyone on schedule, and made sure that the kitchen was stocked with food and that the Bunker was orderly.

At around three in the afternoon, an Icelandic parliamentarian named Birgitta Jonsdottir walked in. Jonsdottir, who is in her forties, with long brown hair and bangs, was wearing a short black skirt and a black T-shirt with skulls printed on it. She took a WikiLeaks T-shirt from her bag and tossed it at Assange.

“That’s for you,” she said. “You need to change.” He put the T-shirt on a chair next to him, and continued working.

Jonsdottir has been in parliament for about a year, but considers herself a poet, artist, writer, and activist. Her political views are mostly anarchist. “I was actually unemployed before I got this job,” she explained. “When we first got to parliament, the staff was so nervous: here are people who were protesting parliament, who were for revolution, and now we are inside. None of us had aspirations to be politicians. We have a checklist, and, once we’re done, we are out.”

As she unpacked her computer, she asked Assange how he was planning to delegate the work on Project B. More Icelandic activists were due to arrive; half a dozen ultimately contributed time to the video, and about as many WikiLeaks volunteers from other countries were participating. Assange suggested that someone make contact with Google to insure that YouTube would host the footage.

“To make sure it is not taken down under pressure?” she asked.

“They have a rule that mentions gratuitous violence,” Assange said. “The violence is not gratuitous in this case, but nonetheless they have taken things down. It is too important to be interfered with.”

“What can we ask M to do?” Jonsdottir asked. Assange, engrossed in what he was doing, didn’t reply.

His concerns about surveillance had not entirely receded. On March 26th, he had written a blast e-mail, titled “Something Is Rotten in the State of Iceland,” in which he described a teen-age Icelandic WikiLeaks volunteer’s story of being detained by local police for more than twenty hours. The volunteer was arrested for trying to break into the factory where his father worked—“the reasons he was trying to get in are not totally justified,” Assange told me—and said that while in custody he was interrogated about Project B. Assange claimed that the volunteer was “shown covert photos of me outside the Reykjavik restaurant Icelandic Fish & Chips,” where a WikiLeaks production meeting had taken place in a private back room.

The police were denying key parts of the volunteer’s story, and Assange was trying to learn more. He received a call, and after a few minutes hung up. “Our young friend talked to one of the cops,” he said. “I was about to get more details, but my battery died.” He smiled and looked suspiciously at his phone.

“We are all paranoid schizophrenics,” Jonsdottir said. She gestured at Assange, who was still wearing his snowsuit. “Just look at how he dresses.”

Gonggrijp got up, walked to the window, and parted the drapes to peer out.

“Someone?” Jonsdottir asked.

“Just the camera van,” he deadpanned. “The brain-manipulation van.”

At around six in the evening, Assange got up from his spot at the table. He was holding a hard drive containing Project B. The video—excerpts of running footage captured by a camera mounted on the Apache—depicts soldiers conducting an operation in eastern Baghdad, not long after the surge began. Using the Freedom of Information Act, Reuters has sought for three years to obtain the video from the Army, without success. Assange would not identify his source, saying only that the person was unhappy about the attack. The video was digitally encrypted, and it took WikiLeaks three months to crack. Assange, a cryptographer of exceptional skill, told me that unlocking the file was “moderately difficult.”

People gathered in front of a computer to watch. In grainy black-and-white, we join the crew of the Apache, from the Eighth Cavalry Regiment, as it hovers above Baghdad with another helicopter. A wide-angle shot frames a mosque’s dome in crosshairs. We see a jumble of buildings and palm trees and abandoned streets. We hear bursts of static, radio blips, and the clipped banter of tactical communication. Two soldiers are in mid-conversation; the first recorded words are “O.K., I got it.” Assange hit the pause button, and said, “In this video, you will see a number of people killed.” The footage, he explained, had three broad phases. “In the first phase, you will see an attack that is based upon a mistake, but certainly a very careless mistake. In the second part, the attack is clearly murder, according to the definition of the average man. And in the third part you will see the killing of innocent civilians in the course of soldiers going after a legitimate target.”

The first phase was chilling, in part because the banter of the soldiers was so far beyond the boundaries of civilian discourse. “Just fuckin’, once you get on ’em, just open ’em up,” one of them said. The crew members of the Apache came upon about a dozen men ambling down a street, a block or so from American troops, and reported that five or six of the men were armed with AK-47s; as the Apache maneuvered into position to fire at them, the crew saw one of the Reuters journalists, who were mixed in among the other men, and mistook a long-lensed camera for an RPG. The Apaches fired on the men for twenty-five seconds, killing nearly all of them instantly.

Phase two began shortly afterward. As the helicopter hovered over the carnage, the crew noticed a wounded survivor struggling on the ground. The man appeared to be unarmed. “All you gotta do is pick up a weapon,” a soldier in the Apache said. Suddenly, a van drove into view, and three unarmed men rushed to help the wounded person. “We have individuals going to the scene, looks like possibly, uh, picking up bodies and weapons,” the Apache reported, even though the men were helping a survivor, and were not collecting weapons. The Apache fired, killing the men and the person they were trying to save, and wounding two young children in the van’s front seat.

In phase three, the helicopter crew radioed a commander to say that at least six armed men had entered a partially constructed building in a dense urban area. Some of the armed men may have walked over from a skirmish with American troops; it is unclear. The crew asked for permission to attack the structure, which they said appeared abandoned. “We can put a missile in it,” a soldier in the Apache suggested, and the go-ahead was quickly given. Moments later, two unarmed people entered the building. Though the soldiers acknowledged them, the attack proceeded: three Hellfire missiles destroyed the building. Passersby were engulfed by clouds of debris.

Assange saw these events in sharply delineated moral terms, yet the footage did not offer easy legal judgments. In the month before the video was shot, members of the battalion on the ground, from the Sixteenth Infantry Regiment, had suffered more than a hundred and fifty attacks and roadside bombings, nineteen injuries, and four deaths; early that morning, the unit had been attacked by small-arms fire. The soldiers in the Apache were matter-of-fact about killing and spoke callously about their victims, but the first attack could be judged as a tragic misunderstanding. The attack on the van was questionable—the use of force seemed neither thoughtful nor measured—but soldiers are permitted to shoot combatants, even when they are assisting the wounded, and one could argue that the Apache’s crew, in the heat of the moment, reasonably judged the men in the van to be assisting the enemy. Phase three may have been unlawful, perhaps negligent homicide or worse. Firing missiles into a building, in daytime, to kill six people who do not appear to be of strategic importance is an excessive use of force. This attack was conducted with scant deliberation, and it is unclear why the Army did not investigate it.

Assange had obtained internal Army records of the operation, which stated that everyone killed, except for the Reuters journalists, was an insurgent. And the day after the incident an Army spokesperson said, “There is no question that Coalition Forces were clearly engaged in combat operations against a hostile force.” Assange was hoping that Project B would undermine the Army’s official narrative. “This video shows what modern warfare has become, and, I think, after seeing it, whenever people hear about a certain number of casualties that resulted during fighting with close air support, they will understand what is going on,” he said in the Bunker. “The video also makes clear that civilians are listed as insurgents automatically, unless they are children, and that bystanders who are killed are not even mentioned.”

WikiLeaks receives about thirty submissions a day, and typically posts the ones it deems credible in their raw, unedited state, with commentary alongside. Assange told me, “I want to set up a new standard: ‘scientific journalism.’ If you publish a paper on DNA, you are required, by all the good biological journals, to submit the data that has informed your research—the idea being that people will replicate it, check it, verify it. So this is something that needs to be done for journalism as well. There is an immediate power imbalance, in that readers are unable to verify what they are being told, and that leads to abuse.” Because Assange publishes his source material, he believes that WikiLeaks is free to offer its analysis, no matter how speculative. In the case of Project B, Assange wanted to edit the raw footage into a short film as a vehicle for commentary. For a while, he thought about calling the film “Permission to Engage,” but ultimately decided on something more forceful: “Collateral Murder.” He told Gonggrijp, “We want to knock out this ‘collateral damage’ euphemism, and so when anyone uses it they will think ‘collateral murder.’ ”

The video, in its original form, was a puzzle—a fragment of evidence divorced from context. Assange and the others in the Bunker spent much of their time trying to piece together details: the units involved, their command structure, the rules of engagement, the jargon soldiers used on the radio, and, most important, whether and how the Iraqis on the ground were armed.

“One of them has a weapon,” Assange said, peering at blurry footage of the men walking down the street. “See all those people standing out there.”

“And there is a guy with an RPG over his arm,” Gonggrijp said.

“I’m not sure.” Assange said. “It does look a little bit like an RPG.” He played the footage again. “I’ll tell you what is very strange,” he said. “If it is an RPG, then there is just one RPG. Where are all the other weapons? All those guys. It is pretty weird.”

The forensic work was made more difficult because Assange had declined to discuss the matter with military officials. “I thought it would be more harmful than helpful,” he told me. “I have approached them before, and, as soon as they hear it is WikiLeaks, they are not terribly coöperative.” Assange was running Project B as a surprise attack. He had encouraged a rumor that the video was shot in Afghanistan in 2009, in the hope that the Defense Department would be caught unprepared. Assange does not believe that the military acts in good faith with the media. He said to me, “What right does this institution have to know the story before the public?”

This adversarial mind-set permeated the Bunker. Late one night, an activist asked if Assange might be detained upon his arrival in the United States.

“If there is ever a time it was safe for me to go, it is now,” Assange assured him.

“They say that Gitmo is nice this time of year,” Gonggrijp said.

Assange was the sole decision-maker, and it was possible to leave the house at night and come back after sunrise and see him in the same place, working. (“I spent two months in one room in Paris once without leaving,” he said. “People were handing me food.”) He spoke to the team in shorthand—“I need the conversion stuff,” or “Make sure that credit-card donations are acceptable”—all the while resolving flareups with the overworked volunteers. To keep track of who was doing what, Gonggrijp and another activist maintained a workflow chart with yellow Post-Its on the kitchen cabinets. Elsewhere, people were translating the video’s subtitles into various languages, or making sure that servers wouldn’t crash from the traffic that was expected after the video was posted. Assange wanted the families of the Iraqis who had died in the attack to be contacted, to prepare them for the inevitable media attention, and to gather additional information. In conjunction with Iceland’s national broadcasting service, RUV, he sent two Icelandic journalists to Baghdad to find them.

By the end of the week, a frame-by-frame examination of the footage was nearly complete, revealing minute details—evidence of a body on the ground, for instance—that were not visible by casual viewing. (“I am about twelve thousand frames in,” the activist who reviewed it told me. “It’s been a morbid day, going through these people’s last moments.”) Assange had decided to exclude the Hellfire incident from the film; the attack lacked the obvious human dimension of the others, and he thought that viewers might be overloaded with information.

The edited film, which was eighteen minutes long, began with a quote from George Orwell that Assange and M had selected: “Political language is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give the appearance of solidity to pure wind.” It then presented information about the journalists who had been killed, and about the official response to the attack. For the audio of this section, one of the film’s Icelandic editors had layered in fragments of radio banter from the soldiers. As Assange reviewed the cut, an activist named Gudmundur Gudmundsson spoke up to say that the banter allowed viewers to “make an emotional bond” with the soldiers. Assange argued that it was mostly fragmentary and garbled, but Gudmundsson insisted: “It is just used all the time for triggering emotions.”

“At the same time, we are displaying them as monsters,” the editor said.

“But emotions always rule,” Gudmundsson said. “By the way, I worked on the sound recording for a film, ‘Children of Nature,’ that was nominated for an Oscar, so I am speaking from experience.”

“Well, what is your alternative?” Assange asked.

“Basically, bursts of sounds, interrupting the quiet,” he said.

The editor made the change, stripping the voices of the soldiers from the opening, but keeping blips and whirs of radio distortion. Assange gave the edit his final approval.

Late Saturday night, shortly before all the work had to be finished, the journalists who had gone to Baghdad sent Assange an e-mail: they had found the two children in the van. The children had lived a block from the location of the attack, and were being driven to school by their father that morning. “They remember the bombardment, felt great pain, they said, and lost consciousness,” one of the journalists wrote. The journalists also found the owner of the building that had been attacked by the Hellfires, who said that families had been living in the structure, and that seven residents had died. The owner, a retired English teacher, had lost his wife and daughter. An intense discussion arose about what to do with this news: Was it worth using at the National Press Club, or was it a better tactic to hold on to it? If the military justified the Hellfire attacks by claiming that there were no civilian casualties, WikiLeaks could respond by releasing the information, in a kind of ambush. Jonsdottir turned to Gonggrijp, whose eyes had welled up.

“Are you crying?” she asked.

“I am,” he said. “O.K., O.K., it is just the kids. It hurts.” Gonggrijp gathered himself. “Fuck!” he said. Resuming the conversation about ambushing the Army, he said, “Anyway, let them walk into this knife—”

“That is a wonderful thing to do,” one of the activists said.

“Let them walk into this, and they will,” Gonggrijp said. “It is a logical response.”

Jonsdottir was now in tears, too, and wiping her nose.

“Now I want to reëdit the thing,” Assange said. “I want to put in the missile attack. There were three families living in the bottom, so it wasn’t abandoned.” But it was impossible to reëdit the film. The activists were working at capacity, and in several hours it would be Easter.

At half past ten in the morning, Gonggrijp pulled open the drapes, and the Bunker was filled with sunlight. He was wearing a long-sleeved T-shirt and black pants, freshly washed and ironed, and he was struggling to keep everyone on schedule. Last-minute concerns—among them finding a criminal-defense lawyer in the United States—were being addressed. Assange was at a computer, his posture upright as he steadily typed.

“How are we on time?” he asked no one in particular.

“We have three hours,” Gonggrijp said.

Assange wrinkled his brow and turned his attention back to the screen. He was looking at a copy of classified rules of engagement in Iraq from 2006, one of several secret American military documents that he was planning to post with the video. WikiLeaks scrubs such documents to insure that no digital traces embedded in them can identify their source. Assange was purging these traces as fast as he could.

Reykjavik’s streets were empty, and the bells of a cathedral began to toll. “Remember, remember the fifth of November,” Assange said, repeating a line from the English folk poem celebrating Guy Fawkes. He smiled, as Gonggrijp dismantled the workflow chart, removing Post-Its from the cabinets and flushing them down the toilet. Shortly before noon, there was a desperate push to clear away the remaining vestiges of Project B and to get to the airport. Assange was unpacked and unshaven, and his hair was a mess. He was typing up a press release. Jonsdottir came by to help, and he asked her, “Can’t you cut my hair while I’m doing this?”

“No, I am not going to cut your hair while you are working,” she said.

Jonsdottir walked over to the sink and made tea. Assange kept on typing, and after a few minutes she reluctantly began to trim his hair. At one point, she stopped and asked, “If you get arrested, will you get in touch with me?” Assange nodded. Gonggrijp, meanwhile, shoved some of Assange’s things into a bag. He settled the bill with the owner. Dishes were washed. Furniture was put back in place. People piled into a small car, and in an instant the house was empty and still.

The name Assange is thought to derive from Ah Sang, or Mr. Sang, a Chinese émigré who settled on Thursday Island, off the coast of Australia, in the early eighteen-hundreds, and whose descendants later moved to the continent. Assange’s maternal ancestors came to Australia in the mid-nineteenth century, from Scotland and Ireland, in search of farmland, and Assange suspects, only half in jest, that his proclivity for wandering is genetic. His phone numbers and e-mail address are ever-changing, and he can drive the people around him crazy with his elusiveness and his propensity to mask details about his life.

Assange was born in 1971, in the city of Townsville, on Australia’s northeastern coast, but it is probably more accurate to say that he was born into a blur of domestic locomotion. Shortly after his first birthday, his mother—I will call her Claire—married a theatre director, and the two collaborated on small productions. They moved often, living near Byron Bay, a beachfront community in New South Wales, and on Magnetic Island, a tiny pile of rock that Captain Cook believed had magnetic properties that distorted his compass readings. They were tough-minded nonconformists. (At seventeen, Claire had burned her schoolbooks and left home on a motorcycle.) Their house on Magnetic Island burned to the ground, and rifle cartridges that Claire had kept for shooting snakes exploded like fireworks. “Most of this period of my childhood was pretty Tom Sawyer,” Assange told me. “I had my own horse. I built my own raft. I went fishing. I was going down mine shafts and tunnels.”

Assange’s mother believed that formal education would inculcate an unhealthy respect for authority in her children and dampen their will to learn. “I didn’t want their spirits broken,” she told me. In any event, the family had moved thirty-seven times by the time Assange was fourteen, making consistent education impossible. He was homeschooled, sometimes, and he took correspondence classes and studied informally with university professors. But mostly he read on his own, voraciously. He was drawn to science. “I spent a lot of time in libraries going from one thing to another, looking closely at the books I found in citations, and followed that trail,” he recalled. He absorbed a large vocabulary, but only later did he learn how to pronounce all the words that he learned.

When Assange was eight, Claire left her husband and began seeing a musician, with whom she had another child, a boy. The relationship was tempestuous; the musician became abusive, she says, and they separated. A fight ensued over the custody of Assange’s half brother, and Claire felt threatened, fearing that the musician would take away her son. Assange recalled her saying, “Now we need to disappear,” and he lived on the run with her from the age of eleven to sixteen. When I asked him about the experience, he told me that there was evidence that the man belonged to a powerful cult called the Family—its motto was “Unseen, Unknown, and Unheard.” Some members were doctors who persuaded mothers to give up their newborn children to the cult’s leader, Anne Hamilton-Byrne. The cult had moles in government, Assange suspected, who provided the musician with leads on Claire’s whereabouts. In fact, Claire often told friends where she had gone, or hid in places where she had lived before.

While on the run, Claire rented a house across the street from an electronics shop. Assange would go there to write programs on a Commodore 64, until Claire bought it for him, moving to a cheaper place to raise the money. He was soon able to crack into well-known programs, where he found hidden messages left by their creators. “The austerity of one’s interaction with a computer is something that appealed to me,” he said. “It is like chess—chess is very austere, in that you don’t have many rules, there is no randomness, and the problem is very hard.” Assange embraced life as an outsider. He later wrote of himself and a teen-age friend, “We were bright sensitive kids who didn’t fit into the dominant subculture and fiercely castigated those who did as irredeemable boneheads.”

When Assange turned sixteen, he got a modem, and his computer was transformed into a portal. Web sites did not exist yet—this was 1987—but computer networks and telecom systems were sufficiently linked to form a hidden electronic landscape that teen-agers with the requisite technical savvy could traverse. Assange called himself Mendax—from Horace’s splendide mendax, or “nobly untruthful”—and he established a reputation as a sophisticated programmer who could break into the most secure networks. He joined with two hackers to form a group that became known as the International Subversives, and they broke into computer systems in Europe and North America, including networks belonging to the U.S. Department of Defense and to the Los Alamos National Laboratory. In a book called “Underground,” which he collaborated on with a writer named Suelette Dreyfus, he outlined the hacker subculture’s early Golden Rules: “Don’t damage computer systems you break into (including crashing them); don’t change the information in those systems (except for altering logs to cover your tracks); and share information.”

Around this time, Assange fell in love with a sixteen-year-old girl, and he briefly moved out of his mother’s home to stay with her. “A couple of days later, police turned up, and they carted off all my computer stuff,” he recalled. The raid, he said, was carried out by the state police, and “it involved some dodgy character who was alleging that we had stolen five hundred thousand dollars from Citibank.” Assange wasn’t charged, and his equipment was returned. “At that point, I decided that it might be wise to be a bit more discreet,” he said. Assange and the girl joined a squatters’ union in Melbourne, until they learned she was pregnant, and moved to be near Claire. When Assange was eighteen, the two got married in an unofficial ceremony, and soon afterward they had a son.

Hacking remained a constant in his life, and the thrill of digital exploration was amplified by the growing knowledge, among the International Subversives, that the authorities were interested in their activities. The Australian Federal Police had set up an investigation into the group, called Operation Weather, which the hackers strove to monitor.

In September, 1991, when Assange was twenty, he hacked into the master terminal that Nortel, the Canadian telecom company, maintained in Melbourne, and began to poke around. The International Subversives had been visiting the master terminal frequently. Normally, Assange hacked into computer systems at night, when they were semi-dormant, but this time a Nortel administrator was signed on. Sensing that he might be caught, Assange approached him with humor. “I have taken control,” he wrote, without giving his name. “For years, I have been struggling in this grayness. But now I have finally seen the light.” The administrator did not reply, and Assange sent another message: “It’s been nice playing with your system. We didn’t do any damage and we even improved a few things. Please don’t call the Australian Federal Police.”

The International Subversives’ incursions into Nortel turned out to be a critical development for Operation Weather. Federal investigators tapped phone lines to see which ones the hackers were using. “Julian was the most knowledgeable and the most secretive of the lot,” Ken Day, the lead investigator, told me. “He had some altruistic motive. I think he acted on the belief that everyone should have access to everything.”

“Underground” describes Assange’s growing fear of arrest: “Mendax dreamed of police raids all the time. He dreamed of footsteps crunching on the driveway gravel, of shadows in the pre-dawn darkness, of a gun-toting police squad bursting through his backdoor at 5 am.” Assange could relax only when he hid his disks in an apiary that he kept. By October, he was in a terrible state. His wife had left him, taking with her their infant son. His home was a mess. He barely ate or slept. On the night the police came, the twenty-ninth, he wired his phone through his stereo and listened to the busy signal until eleven-thirty, when Ken Day knocked on his door, and told him, “I think you’ve been expecting me.”

Assange was charged with thirty-one counts of hacking and related crimes. While awaiting trial, he fell into a depression, and briefly checked himself into a hospital. He tried to stay with his mother, but after a few days he took to sleeping in nearby parks. He lived and hiked among dense eucalyptus forests in the Dandenong Ranges National Park, which were thick with mosquitoes whose bites scarred his face. “Your inner voice quiets down,” he told me. “Internal dialogue is stimulated by a preparatory desire to speak, but it is not actually useful if there are no other people around.” He added, “I don’t want to sound too Buddhist. But your vision of yourself disappears.”

It took more than three years for the authorities to bring the case against Assange and the other International Subversives to court. Day told me, “We had just formed the computer-crimes team, and the government said, ‘Your charter is to establish a deterrent.’ Well, to get a deterrent you have to prosecute people, and we achieved that with Julian and his group.” A computer-security team working for Nortel in Canada drafted an incident report alleging that the hacking had caused damage that would cost more than a hundred thousand dollars to repair. The chief prosecutor, describing Assange’s near-limitless access, told the court, “It was God Almighty walking around doing what you like.”

Assange, facing a potential sentence of ten years in prison, found the state’s reaction confounding. He bought Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s “The First Circle,” a novel about scientists and technicians forced into the Gulag, and read it three times. (“How close the parallels to my own adventures!” he later wrote.) He was convinced that “look/see” hacking was a victimless crime, and intended to fight the charges. But the other members of the group decided to coöperate. “When a judge says, ‘The prisoner shall now rise,’ and no one else in the room stands—that is a test of character,” he told me. Ultimately, he pleaded guilty to twenty-five charges and six were dropped. But at his final sentencing the judge said, “There is just no evidence that there was anything other than sort of intelligent inquisitiveness and the pleasure of being able to—what’s the expression—surf through these various computers.” Assange’s only penalty was to pay the Australian state a small sum in damages.

As the criminal case was unfolding, Assange and his mother were also waging a campaign to gain full custody of Assange’s son—a legal fight that was, in many ways, far more wrenching than his criminal defense. They were convinced that the boy’s mother and her new boyfriend posed a danger to the child, and they sought to restrict her rights. The state’s child-protection agency, Health and Community Services, disagreed. The specifics of the allegations are unclear; family-court records in Australia are kept anonymous. But in 1995 a parliamentary committee found that the agency maintained an “underlying philosophy of deflecting as many cases away from itself as possible.” When the agency decided that a child was living in a safe household, there was no way to immediately appeal its decision.

The custody battle evolved into a bitter fight with the state. “What we saw was a great bureaucracy that was squashing people,” Claire told me. She and Assange, along with another activist, formed an organization called Parent Inquiry Into Child Protection. “We used full-on activist methods,” Claire recalled. In meetings with Health and Community Services, “we would go in and tape-record them secretly.” The organization used the Australian Freedom of Information Act to obtain documents from Health and Community Services, and they distributed flyers to child-protection workers, encouraging them to come forward with inside information, for a “central databank” that they were creating. “You may remain anonymous if you wish,” one flyer stated. One protection worker leaked to the group an important internal manual. Assange told me, “We had moles who were inside dissidents.”

In 1999, after nearly three dozen legal hearings and appeals, Assange worked out a custody agreement with his wife. Claire told me, “We had experienced very high levels of adrenaline, and I think that after it all finished I ended up with P.T.S.D. It was like coming back from a war. You just can’t interact with normal people to the same degree, and I am sure that Jules has some P.T.S.D. that is untreated.” Not long after the court cases, she said, Assange’s hair, which had been dark brown, became drained of all color.

Assange was burned out. He motorcycled across Vietnam. He held various jobs, and even earned money as a computer-security consultant, supporting his son to the extent that he was able. He studied physics at the University of Melbourne. He thought that trying to decrypt the secret laws governing the universe would provide the intellectual stimulation and rush of hacking. It did not. In 2006, on a blog he had started, he wrote about a conference organized by the Australian Institute of Physics, “with 900 career physicists, the body of which were sniveling fearful conformists of woefully, woefully inferior character.”

He had come to understand the defining human struggle not as left versus right, or faith versus reason, but as individual versus institution. As a student of Kafka, Koestler, and Solzhenitsyn, he believed that truth, creativity, love, and compassion are corrupted by institutional hierarchies, and by “patronage networks”—one of his favorite expressions—that contort the human spirit. He sketched out a manifesto of sorts, titled “Conspiracy as Governance,” which sought to apply graph theory to politics. Assange wrote that illegitimate governance was by definition conspiratorial—the product of functionaries in “collaborative secrecy, working to the detriment of a population.” He argued that, when a regime’s lines of internal communication are disrupted, the information flow among conspirators must dwindle, and that, as the flow approaches zero, the conspiracy dissolves. Leaks were an instrument of information warfare.

These ideas soon evolved into WikiLeaks. In 2006, Assange barricaded himself in a house near the university and began to work. In fits of creativity, he would write out flow diagrams for the system on the walls and doors, so as not to forget them. There was a bed in the kitchen, and he invited backpackers passing through campus to stay with him, in exchange for help building the site. “He wouldn’t sleep at all,” a person who was living in the house told me. “He wouldn’t eat.”

As it now functions, the Web site is primarily hosted on a Swedish Internet service provider called PRQ.se, which was created to withstand both legal pressure and cyber attacks, and which fiercely preserves the anonymity of its clients. Submissions are routed first through PRQ, then to a WikiLeaks server in Belgium, and then on to “another country that has some beneficial laws,” Assange told me, where they are removed at “end-point machines” and stored elsewhere. These machines are maintained by exceptionally secretive engineers, the high priesthood of WikiLeaks. One of them, who would speak only by encrypted chat, told me that Assange and the other public members of WikiLeaks “do not have access to certain parts of the system as a measure to protect them and us.” The entire pipeline, along with the submissions moving through it, is encrypted, and the traffic is kept anonymous by means of a modified version of the Tor network, which sends Internet traffic through “virtual tunnels” that are extremely private. Moreover, at any given time WikiLeaks computers are feeding hundreds of thousands of fake submissions through these tunnels, obscuring the real documents. Assange told me that there are still vulnerabilities, but “this is vastly more secure than any banking network.”

Before launching the site, Assange needed to show potential contributors that it was viable. One of the WikiLeaks activists owned a server that was being used as a node for the Tor network. Millions of secret transmissions passed through it. The activist noticed that hackers from China were using the network to gather foreign governments’ information, and began to record this traffic. Only a small fraction has ever been posted on WikiLeaks, but the initial tranche served as the site’s foundation, and Assange was able to say, “We have received over one million documents from thirteen countries.”

In December, 2006, WikiLeaks posted its first document: a “secret decision,” signed by Sheikh Hassan Dahir Aweys, a Somali rebel leader for the Islamic Courts Union, that had been culled from traffic passing through the Tor network to China. The document called for the execution of government officials by hiring “criminals” as hit men. Assange and the others were uncertain of its authenticity, but they thought that readers, using Wikipedia-like features of the site, would help analyze it. They published the decision with a lengthy commentary, which asked, “Is it a bold manifesto by a flamboyant Islamic militant with links to Bin Laden? Or is it a clever smear by US intelligence, designed to discredit the Union, fracture Somali alliances and manipulate China?”

The document’s authenticity was never determined, and news about WikiLeaks quickly superseded the leak itself. Several weeks later, Assange flew to Kenya for the World Social Forum, an anti-capitalist convention, to make a presentation about the Web site. “He packed in the funniest way I have ever seen,” the person who had been living in the house recalled. “Someone came to pick him up, and he was asked, ‘Where is your luggage?’ And he ran back into the house. He had a sailor’s sack, and he grabbed a whole bunch of stuff and threw it in there, mostly socks.”

Assange ended up staying in Kenya for several months. He would check in with friends by phone and through the Internet from time to time, but was never precise about his movements. One friend told me, “It would always be, ‘Where is Julian?’ It was always difficult to know where he was. It was almost like he was trying to hide.”

It took about an hour on Easter morning to get from the house on Grettisgata Street to Iceland’s international airport, which is situated on a lava field by the sea. Assange, in the terminal, carried a threadbare blue backpack that contained hard drives, phone cards, and multiple cell phones. Gonggrijp had agreed to go to Washington to help with the press conference. He checked in, and the ticketing agent turned to Assange.

“I am sorry,” she said to him. “I cannot find your name.”

“Interesting,” Assange said to Gonggrijp. “Have fun at the press conference.”

“No,” Gonggrijp told the attendant. “We have a booking I.D. number.”

“It’s been confirmed,” Assange insisted.

The attendant looked perplexed. “I know,” she said. “But my booking information has it ‘cancelled.’ ”

The two men exchanged a look: was a government agency tampering with their plans? Assange waited anxiously, but it turned out that he had bought the ticket and neglected to confirm the purchase. He quickly bought another ticket, and the two men flew to New York and then rushed to catch the Acela to Washington. It was nearly two in the morning when they arrived. They got into a taxi, and Assange, who didn’t want to reveal the location of his hotel, told the driver to go to a nearby cross street.

“Here we are in the lion’s den,” Gonggrijp said as the taxi raced down Massachusetts Avenue, passing rows of nondescript office buildings. Assange said, “Not looking too lionish.”

A few hours after sunrise, Assange was standing at a lectern inside the National Press Club, ready to present “Collateral Murder” to the forty or so journalists who had come. He was dressed in a brown blazer, a black shirt, and a red tie. He played the film for the audience, pausing it to discuss various details. After the film ended, he ran footage of the Hellfire attack—a woman in the audience gasped as the first missile hit the building—and read from the e-mail sent by the Icelandic journalists who had gone to Iraq. The leak, he told the reporters, “sends a message that some people within the military don’t like what is going on.”

The video, in both raw and edited forms, was released on the site that WikiLeaks had built for it, and also on YouTube and a number of other Web sites. Within minutes after the press conference, Assange was invited to Al Jazeera’s Washington headquarters, where he spent half the day giving interviews, and that evening MSNBC ran a long segment about the footage. The video was covered in the Times, in multiple stories, and in every other major paper. On YouTube alone, more than seven million viewers have watched “Collateral Murder.”

Defense Secretary Robert Gates was asked about the footage, and said, clearly irritated, “These people can put anything out they want and are never held accountable for it.” The video was like looking at war “through a soda straw,” he said. “There is no before and there is no after.” Army spokespeople insisted that there was no violation of the rules of engagement. At first, the media’s response hewed to Assange’s interpretation, but, in the ensuing days, as more commentators weighed in and the military offered its view, Assange grew frustrated. Much of the coverage focussed not on the Hellfire attack or the van but on the killing of the journalists and on how a soldier might reasonably mistake a camera for an RPG. On Twitter, Assange accused Gates of being “a liar,” and beseeched members of the media to “stop spinning.”

In some respects, Assange appeared to be most annoyed by the journalistic process itself—“a craven sucking up to official sources to imbue the eventual story with some kind of official basis,” as he once put it. WikiLeaks has long maintained a complicated relationship with conventional journalism. When, in 2008, the site was sued after publishing confidential documents from a Swiss bank, the Los Angeles Times, the Associated Press, and ten other news organizations filed amicus briefs in support. (The bank later withdrew its suit.) But, in the Bunker one evening, Gonggrijp told me, “We are not the press.” He considers WikiLeaks an advocacy group for sources; within the framework of the Web site, he said, “the source is no longer dependent on finding a journalist who may or may not do something good with his document.”

Assange, despite his claims to scientific journalism, emphasized to me that his mission is to expose injustice, not to provide an even-handed record of events. In an invitation to potential collaborators in 2006, he wrote, “Our primary targets are those highly oppressive regimes in China, Russia and Central Eurasia, but we also expect to be of assistance to those in the West who wish to reveal illegal or immoral behavior in their own governments and corporations.” He has argued that a “social movement” to expose secrets could “bring down many administrations that rely on concealing reality—including the US administration.”

Assange does not recognize the limits that traditional publishers do. Recently, he posted military documents that included the Social Security numbers of soldiers, and in the Bunker I asked him if WikiLeaks’ mission would have been compromised if he had redacted these small bits. He said that some leaks risked harming innocent people—“collateral damage, if you will”—but that he could not weigh the importance of every detail in every document. Perhaps the Social Security numbers would one day be important to researchers investigating wrongdoing, he said; by releasing the information he would allow judgment to occur in the open.

A year and a half ago, WikiLeaks published the results of an Army test, conducted in 2004, of electromagnetic devices designed to prevent IEDs from being triggered. The document revealed key aspects of how the devices functioned and also showed that they interfered with communication systems used by soldiers—information that an insurgent could exploit. By the time WikiLeaks published the study, the Army had begun to deploy newer technology, but some soldiers were still using the devices. I asked Assange if he would refrain from releasing information that he knew might get someone killed. He said that he had instituted a “harm-minimization policy,” whereby people named in certain documents were contacted before publication, to warn them, but that there were also instances where the members of WikiLeaks might get “blood on our hands.”

One member told me that Assange’s editorial policy initially made her uncomfortable, but that she has come around to his position, because she believes that no one has been unjustly harmed. Of course, such harm is not always easy to measure. When Assange was looking for board members, he contacted Steven Aftergood, who runs an e-mail newsletter for the Federation of American Scientists, and who publishes sensitive documents. Aftergood declined to participate. “When a technical record is both sensitive and remote from a current subject of controversy, my editorial inclination is to err on the side of caution,” he said. “I miss that kind of questioning on their part.”

At the same time, Aftergood told me, the overclassification of information is a problem of increasing scale—one that harms not only citizens, who should be able to have access to government records, but the system of classification itself. When too many secrets are kept, it becomes difficult to know which ones are important. Had the military released the video from the Apache to Reuters under FOIA, it would probably not have become a film titled “Collateral Murder,” and a public-relations nightmare.

Lieutenant Colonel Lee Packnett, the spokesperson for intelligence matters for the Army, was deeply agitated when I called him. “We’re not going to give validity to WikiLeaks,” he said. “You’re not doing anything for the Army by putting us in a conversation about WikiLeaks. You can talk to someone else. It’s not an Army issue.” As he saw it, once “Collateral Murder” had passed through the news cycle, the broader counter-intelligence problem that WikiLeaks poses to the military had disappeared as well. “It went away,” he said.

With the release of “Collateral Murder,” WikiLeaks received more than two hundred thousand dollars in donations, and on April 7th Assange wrote on Twitter, “New funding model for journalism: try doing it for a change.” Just this winter, he had put the site into a state of semi-dormancy because there was not enough money to run it, and because its technical engineering needed adjusting. Assange has far more material than he can process, and he is seeking specialists who can sift through the chaotic WikiLeaks library and assign documents to volunteers for analysis. The donations meant that WikiLeaks would now be able to pay some volunteers, and in late May its full archive went back online. Still, the site remains a project in early development. Assange has been searching for the right way not only to manage it but also to get readers interested in the more arcane material there.

In 2007, he published thousands of pages of secret military information detailing a vast number of Army procurements in Iraq and Afghanistan. He and a volunteer spent weeks building a searchable database, studying the Army’s purchasing codes, and adding up the cost of the procurements—billions of dollars in all. The database catalogued matériel that every unit had ordered: machine guns, Humvees, cash-counting machines, satellite phones. Assange hoped that journalists would pore through it, but barely any did. “I am so angry,” he said. “This was such a fucking fantastic leak: the Army’s force structure of Afghanistan and Iraq, down to the last chair, and nothing.”

WikiLeaks is a finalist for a Knight Foundation grant of more than half a million dollars. The intended project would set up a way for sources to pass documents to newspaper reporters securely; WikiLeaks would serve as a kind of numbered Swiss bank account, where information could be anonymously exchanged. (The system would allow the source to impose a deadline on the reporter, after which the document would automatically appear on WikiLeaks.) Assange has been experimenting with other ideas, too. On the principle that people won’t regard something as valuable unless they pay for it, he has tried selling documents at auction to news organizations; in 2008, he attempted this with seven thousand internal e-mails from the account of a former speechwriter for Hugo Chávez. The auction failed. He is thinking about setting up a subscription service, where high-paying members would have early access to leaks.

But experimenting with the site’s presentation and its technical operations will not answer a deeper question that WikiLeaks must address: What is it about? The Web site’s strengths—its near-total imperviousness to lawsuits and government harassment—make it an instrument for good in societies where the laws are unjust. But, unlike authoritarian regimes, democratic governments hold secrets largely because citizens agree that they should, in order to protect legitimate policy. In liberal societies, the site’s strengths are its weaknesses. Lawsuits, if they are fair, are a form of deterrence against abuse. Soon enough, Assange must confront the paradox of his creation: the thing that he seems to detest most—power without accountability—is encoded in the site’s DNA, and will only become more pronounced as WikiLeaks evolves into a real institution.

After the press conference in Washington, I met Assange in New York, in Bryant Park. He had brought his luggage with him, because he was moving between the apartments of friends of friends. We sat near the fountain, and drank coffee. That week, Assange was scheduled to fly to Berkeley, and then to Italy, but back in Iceland the volcano was erupting again, and his flight to Europe was likely to change. He looked a bit shell-shocked. “It was surprising to me that we were seen as such an impartial arbiter of the truth, which may speak well to what we have done,” he told me. But he also said, “To be completely impartial is to be an idiot. This would mean that we would have to treat the dust in the street the same as the lives of people who have been killed.”

A number of commentators had wondered whether the video’s title was manipulative. “In hindsight, should we have called it ‘Permission to Engage’ rather than ‘Collateral Murder’?” he said. “I’m still not sure.” He was annoyed by Gates’s comment on the film: “He says, ‘There is no before and no after.’ Well, at least there is now a middle, which is a vast improvement.” Then Assange leaned forward and, in a whisper, began to talk about a leak, code-named Project G, that he is developing in another secret location. He promised that it would be news, and I saw in him the same mixture of seriousness and amusement, devilishness and intensity that he had displayed in the Bunker. “If it feels a little bit like we’re amateurs, it is because we are,” he said. “Everyone is an amateur in this business.” And then, his coffee finished, he made his way out of the park and into Times Square, disappearing among the masses of people moving this way and that. ♦

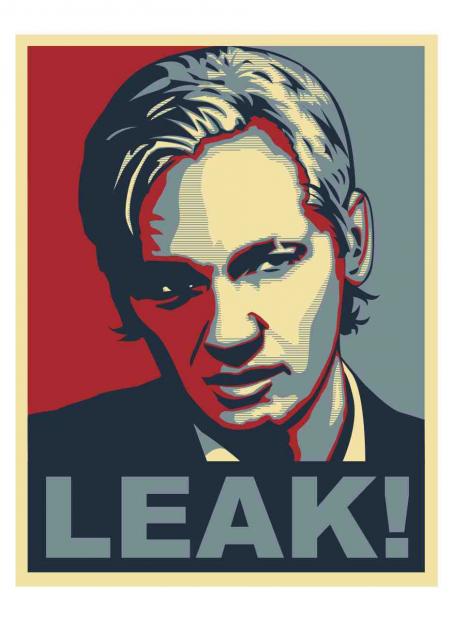

Portrait of Wikileaks founder Julian Assange by artist Arjen van Lith

Portrait of Wikileaks founder Julian Assange by artist Arjen van Lith